- I took on our long-term Rivian R1T electric pickup on a road trip from Los Angeles to Monterey.

- My successes in charging the R1T on the road were limited.

- Even at this stage, charging a non-Tesla vehicle remains a significant challenge.

If You’re Road-Tripping an EV, the Only Choice Is Tesla

A simple road trip turns into an unnecessary odyssey

“Are you planning to charge to 100%?” I asked with as much charm as I could muster at 10:30 p.m. “Probably not,” said the gentleman in the Polestar 2, “but my wife wants to finish a documentary. We’ve never had a car that you can watch TV in before.” With the Polestar’s battery more than 90% full, the 150-kW “fast” charger was now outputting just 6 kW. In a Polestar 2, that’s adding about 30 miles per hour.

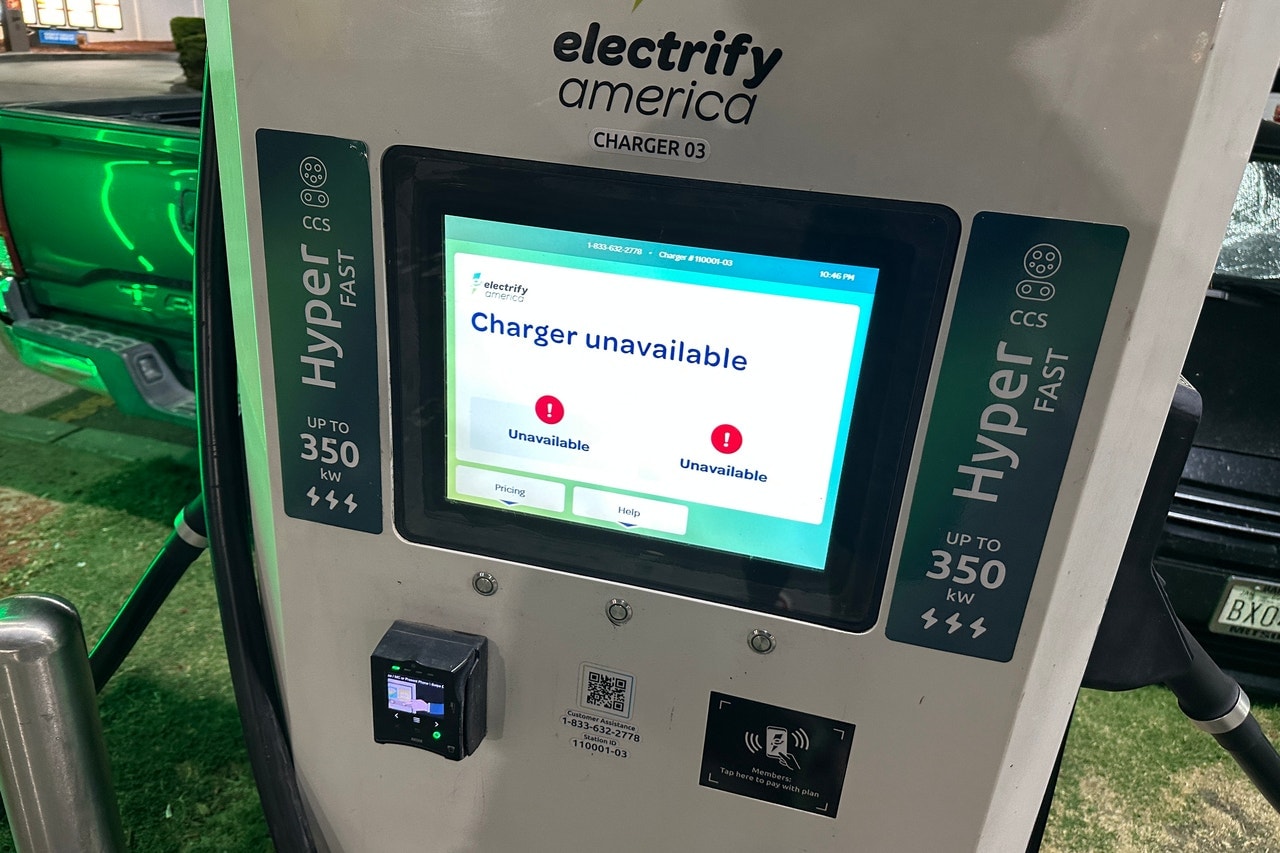

This wouldn’t have mattered if any of the 350-kW Electrify America chargers in Lost Hills, California, had been working, but all four were broken. I was taking a road trip in Edmunds’ long-term Rivian R1T, and it needed electrons. Our only viable option was to wait. “Remind me again why you thought it’d be a good idea to bring an electric truck on a family vacation?” asked my wife, not unreasonably. “I want to go to bed, and the kids are going to wake up any minute.”

For road-tripping EV owners, this has become an all-too familiar experience. Ford CEO Jim Farley recently admitted to a “reality check” while attempting to drive an F-150 Lightning long-distance. “Charging has been pretty challenging,” he told his roughly 250,000 followers on X. And this was in California, the poster child of the EV revolution, where 17% of new cars sold are now fueled by a plug.

U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm recently apologized for a spectacular faux pas when a staffer tried to reserve an EV charger for their boss by using a gas car to block the space. A family was so incensed by this "ICEing" they called the cops. Granholm, who, ironically, had been attempting to promote EV adoption across the southeastern states, admitted that long-distance EV travel for non-Tesla owners was not “super-easy.”

By focusing too heavily on range anxiety — how far a vehicle will travel on a single charge — the auto industry has missed the point. As an analysis of Edmunds EV Range Test data shows, almost all modern EVs have a real-world range of well over 200 miles — the Rivian achieved 321 miles on our real-world EV range test. This would be ample if there was a reliable, plentiful fast-charging infrastructure.

My experience didn’t improve. After adding 40 miles of charge to the R1T in Lost Hills, my toddlers woke up and started screaming, prompting us to abandon the enterprise. Next morning, the solitary working charger was occupied by a Ford F-150 Lightning and would be out of action for at least an hour.

Our destination hotel had just two domestic-style Level 2 chargers for 90 rooms, with fully electric vehicles competing for charge with plug-in hybrids. “We’re trying to install more,” the manager told me, “but it’s logistically challenging.” Attempts to charge in the city of Monterey were thwarted by locked city gates (it being a weekend) and a hotel that wanted $60 to enter a parking garage with no guarantee of an available plug.

On the way back to Los Angeles, we stopped at a 350-kW Electrify America charger in the city of Paso Robles. It would take an hour to achieve the charge we needed in the Rivian, the least efficient EV Edmunds has ever tested. We went for lunch, but the service was slow and the kids needed to potty. It was 90 minutes before we returned to the truck, to be met by an angry note on red paper attached to the windscreen. “I sat here for 20 minutes waiting for you … Please think of others next time.” If you’re reading this, sorry.

For car manufacturers, this is an entirely different kind of challenge. For 130 years, they built a product and relied on others to handle the infrastructure. The expectation was the same with the birth of the electric car, but it’s proved erroneous. Many thought Tesla mad to build a charging network as well as a car, but it now looks like an act of genius. That’s why so many manufacturers are now pooling resources to try to fix the problem themselves, or to jump into bed with Elon, whose proprietary plug looks set to become the VHS of the 21st century.

It remains to be seen how successful these initiatives will be, and how frustrated Tesla customers will get when they find a Ford using their beloved Supercharger. Farley and Granholm were being diplomatic — EV fast charging in the U.S. is not "challenging," it’s a shambles. The "reality check" is real and there’s no overnight fix. Right now, the infrastructure, not the product or the pricing, is the biggest barrier to widespread EV adoption. The problem is not range anxiety, it’s charging anxiety.

Edmunds says

EV manufacturers not named Tesla have ignored charging infrastructure for far too long.

by

by